The Unfolding History Of Collage In Modern Art

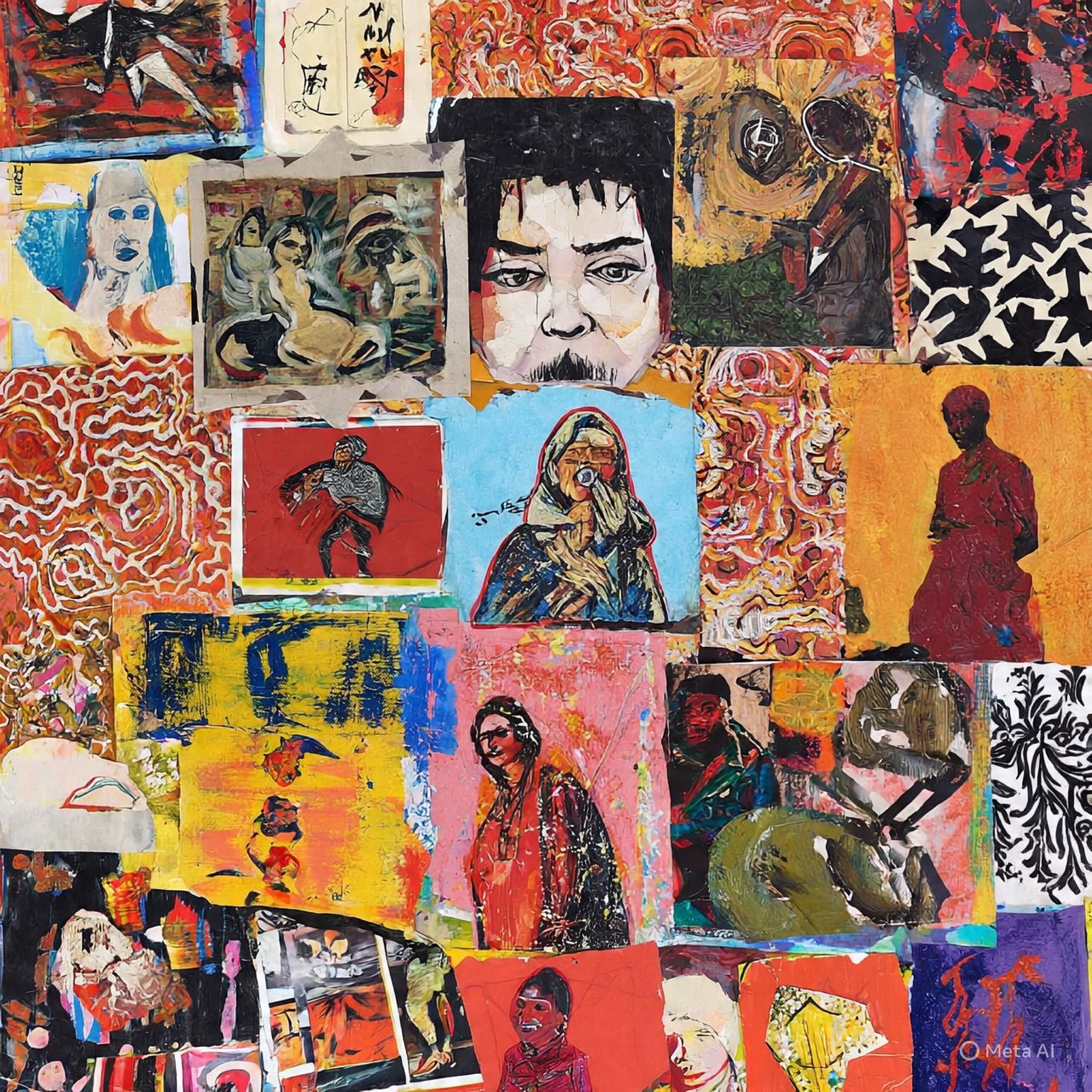

The Evolution of Collage in Modern Art

Collage, an art form born from the juxtaposition of disparate materials, has been a transformative medium throughout modern art history. Its evolution is intrinsically linked to visionary artists and groundbreaking movements that pushed the boundaries of traditional artistic expression.

The Cubist Pioneers Picasso and Braque

The origins of collage as a fine art medium are often attributed to the Cubist movement in the early 20th century. In 1912, Pablo Picasso incorporated a piece of oilcloth printed with a chair caning pattern into his work *Still Life with Chair Caning*, marking the first instance of a *papier collé* (pasted paper) in painting. This revolutionary act challenged the notions of reality and representation in art [MoMA]. Shortly after, Georges Braque, Picasso’s collaborator in Cubism, also began integrating pasted papers into his charcoal drawings, further solidifying collage as a legitimate artistic technique [Tate]. Their innovative use of everyday materials like newspaper clippings and wallpaper fragments introduced a new dimension of texture and meaning to their artworks, fundamentally altering the landscape of visual art.

Dada’s Disruptive Spirit Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann

Following Cubism, collage found a potent voice in the anti-establishment Dada movement, which emerged in response to the horrors of World War I. Dada artists embraced collage, particularly photomontage, as a tool for social and political critique. German artist Hannah Höch was a pioneering figure in this regard, using fragmented photographic images from magazines and newspapers to create powerful, often satirical, commentaries on gender, politics, and modern society [The Metropolitan Museum of Art]. Her work, such as *Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany* (1919), epitomizes the Dadaist spirit of deconstruction and reassembly. Raoul Hausmann, another prominent Dadaist, also explored photomontage to express the chaos and absurdity of post-war Europe, challenging conventional artistic norms [MoMA].

Surrealism’s Dreamscapes Max Ernst

The Surrealist movement, which evolved from Dada, saw collage as an ideal method to explore the subconscious mind and dream imagery. Artists like Max Ernst developed techniques such as “frottage” and “decalcomania,” but also famously created captivating collage novels, including *La Femme 100 Têtes* (The Hundred Headless Woman) [Artstor]. By juxtaposing images from Victorian etchings and scientific illustrations, Ernst crafted unsettling and fantastical narratives that evoked the illogical nature of dreams and challenged conventional reality, inviting viewers into a realm beyond consciousness.

Pop Art’s Consumer Culture Critique Richard Hamilton

In the mid-20th century, Pop Art emerged, utilizing collage to reflect on mass media, advertising, and consumer culture. British artist Richard Hamilton’s iconic work, *Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?* (1956), is considered a foundational piece of Pop Art. This small but impactful collage, assembled from magazine clippings, satirized the idealized modern consumer lifestyle and laid bare the visual language of advertising [MoMA]. His work, alongside that of Eduardo Paolozzi, solidified collage as a primary tool for engaging with contemporary visual culture and critiquing its pervasive influence. From its radical beginnings in Cubism to its critical role in Dada, Surrealism, and Pop Art, collage has consistently provided artists with a powerful means to re-contextualize images, challenge perceptions, and create new narratives, solidifying its place as a cornerstone of modern and contemporary art.

The Transformative Power of Undergraduate Research

Engaging in undergraduate research is a cornerstone experience for many students, offering a unique opportunity to delve into real-world problems and contribute to new knowledge. Far beyond textbook learning, these experiences provide invaluable hands-on training, critical thinking skills, and a deeper understanding of academic disciplines [Nature]. Students involved in research often work closely with faculty mentors, applying classroom theories to practical investigations and developing a research mindset. This direct engagement fosters intellectual curiosity and prepares students for diverse career paths and advanced studies.

The benefits of participating in research extend significantly beyond the lab or field. Students develop a comprehensive set of transferable skills, including problem-solving, data analysis, critical evaluation, and effective communication [NCBI]. These competencies are highly sought after by employers across various sectors and are essential for success in graduate school programs. For instance, participating in research can significantly enhance applications for graduate programs by demonstrating initiative, a strong work ethic, and an ability to conduct independent scholarly work [Sage Journals]. It also provides a clear pathway for students to make an impact with their research, presenting their findings at events like Research and Creative Activity Day or applying for travel awards to showcase their work at conferences.

Opportunities for undergraduate research are diverse, spanning all academic fields from sciences and engineering to humanities and social sciences. Many institutions offer structured programs, research grants like the Gavin Migratory Bird Research Grant, and workshops on topics such as responsible conduct of research training and grant writing to support students in their research endeavors. Engaging in research allows students to explore potential career interests, build professional networks, and gain a competitive edge in their chosen fields. It’s an investment in intellectual growth and future success.

Navigating Academic Research Funding

Academic research funding, often secured through grants, is a vital component for both students and faculty in advancing knowledge and innovation. These funds provide essential resources for projects, enabling the acquisition of equipment, travel for fieldwork, stipends for researchers, and access to critical data and facilities [Nature]. Securing grants can significantly boost a researcher’s career, offering opportunities to conduct impactful studies, publish findings, and contribute to their respective fields [National Institutes of Health].

For students, grants, like travel awards, can support participation in conferences, field research, or the development of thesis projects [National Science Foundation]. Faculty members often pursue larger grants to establish research labs, fund long-term studies, and support graduate students [NCBI]. Institutions typically have offices dedicated to research and sponsored programs that assist with identifying opportunities, proposal development, and managing awards.

The process of obtaining a grant typically involves identifying a suitable funding opportunity, carefully reviewing the guidelines, developing a detailed research proposal, crafting a realistic budget, and submitting the application by the deadline [ScienceDirect]. Many universities also offer resources like free courses on proposal planning and grant writing to help researchers hone their application skills. Exploring diverse funding sources, from federal agencies like the National Science Foundation (NSF) or National Institutes of Health (NIH) to private foundations and institutional programs, is crucial [Grants.gov]. Opportunities for specific research areas, such as the Gavin Migratory Bird Research Grant, are often available. Students can also seek support through programs like URSA Travel Awards to enhance their research experiences and make an impact with their work.

The Remarkable Adaptations of the Moose’s Muzzle

The imposing size of a moose’s nose, or muzzle, is a remarkable adaptation that serves multiple vital functions, distinguishing it from other cervids and proving essential for its survival in diverse environments. Far from being merely a prominent feature, this specialized snout plays a vital role in foraging, olfaction, and even thermoregulation.

One of the primary purposes of the moose’s large nose is its exceptional olfactory capabilities. Their keen sense of smell, facilitated by a complex nasal structure, is crucial for detecting predators, locating mates during breeding season, and finding food sources, even those hidden under snow or water [Wildlife Informer]. Its large nasal cavity houses a vast surface area of olfactory membranes, enabling them to identify potential mates and food from considerable distances [National Geographic]. This heightened olfaction is particularly important in their often dense, forested habitats where visibility can be limited.

Beyond smell, the moose’s nose is uniquely adapted for its semi-aquatic lifestyle and feeding habits. Moose are known to dive underwater to feed on aquatic vegetation, a highly nutritious part of their diet. Their powerful, prehensile upper lip and nostrils, which can be closed to prevent water entry, allow them to efficiently grasp and pull up plants from the bottom of lakes and ponds while submerged [Untamed Animals]. The sheer size of the muzzle provides the necessary strength and dexterity for this underwater foraging, enabling them to tear plants like water lilies and pondweed without inhaling water [Wildlife Informer].

Furthermore, the large surface area and complex network of blood vessels within the moose’s nose contribute significantly to thermoregulation. Moose are well-insulated and can overheat, especially during strenuous activity or in warmer months. The extensive network of blood vessels within their muzzles helps to dissipate excess body heat, acting as a natural cooling system [Wildlife Informer]. As blood flows through the capillaries in the nose, heat can be released to the cooler air or water, helping the animal maintain a stable body temperature [Adirondack Almanack]. This feature is particularly beneficial given their large body mass and the cold environments they inhabit, where conserving energy is key. Thus, the moose’s large nose is not merely a prominent feature but a highly specialized organ essential for its unique lifestyle and survival.

Sources

- Adirondack Almanack – The Moose Nose: A Design Masterpiece

- Art Institute of Chicago – Georges Braque

- Artstor – Max Ernst: A Surrealist Pioneer of Collage

- Britannica – Hannah Höch

- Grants.gov – Find Grant Programs

- Guggenheim – Max Ernst

- Sage Journals – Benefits of Undergraduate Research Experiences for STEM Students

- King’s College – Call for Undergraduate Student Submissions: URSA’s Research and Creative Activity Day

- King’s College – Free Proposal Planning and Grant Writing Courses Now Available on AlaskaX

- King’s College – Gavin Migratory Bird Research Grant Applications Due By Dec. 12

- King’s College – Make an Impact with Your Research

- King’s College – Responsible Conduct of Research Training: March 25

- King’s College – URSA Spring 2022 Travel Awards

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Hannah Höch: Artist Page

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Pablo Picasso: Artist Page

- MoMA – Pablo Picasso. Still Life with Chair Caning. Paris, May 1912

- MoMA – Richard Hamilton. Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? 1956

- MoMA – Raoul Hausmann

- National Geographic – Moose Facts

- National Institutes of Health – NIH Grants Policy Statement

- National Science Foundation – Graduate Research Fellowship Program (GRFP)

- Nature – Navigating academic research funding

- Nature – The undergraduate research experience can be transformational

- NCBI – Grant Writing for Junior Researchers

- NCBI – Outcomes of Undergraduate Research: An Empirical Analysis

- ScienceDirect – Grant Writing: A Complete Guide for Scholars

- Tate – Collage

- Tate – Eduardo Paolozzi

- Tate – Raoul Hausmann

- Tate – Richard Hamilton

- Untamed Animals – Why Do Moose Have Big Noses?

- Wildlife Informer – Why Do Moose Have Big Noses? (And 5 More Facts)

From Picasso’s Cubist experiments to Pop Art’s consumer critiques, collage has continually reshaped modern art, offering fresh ways to question reality and culture. Likewise, research and discovery—from student innovation to the moose’s remarkable adaptations—show how creativity and inquiry drive progress across disciplines.